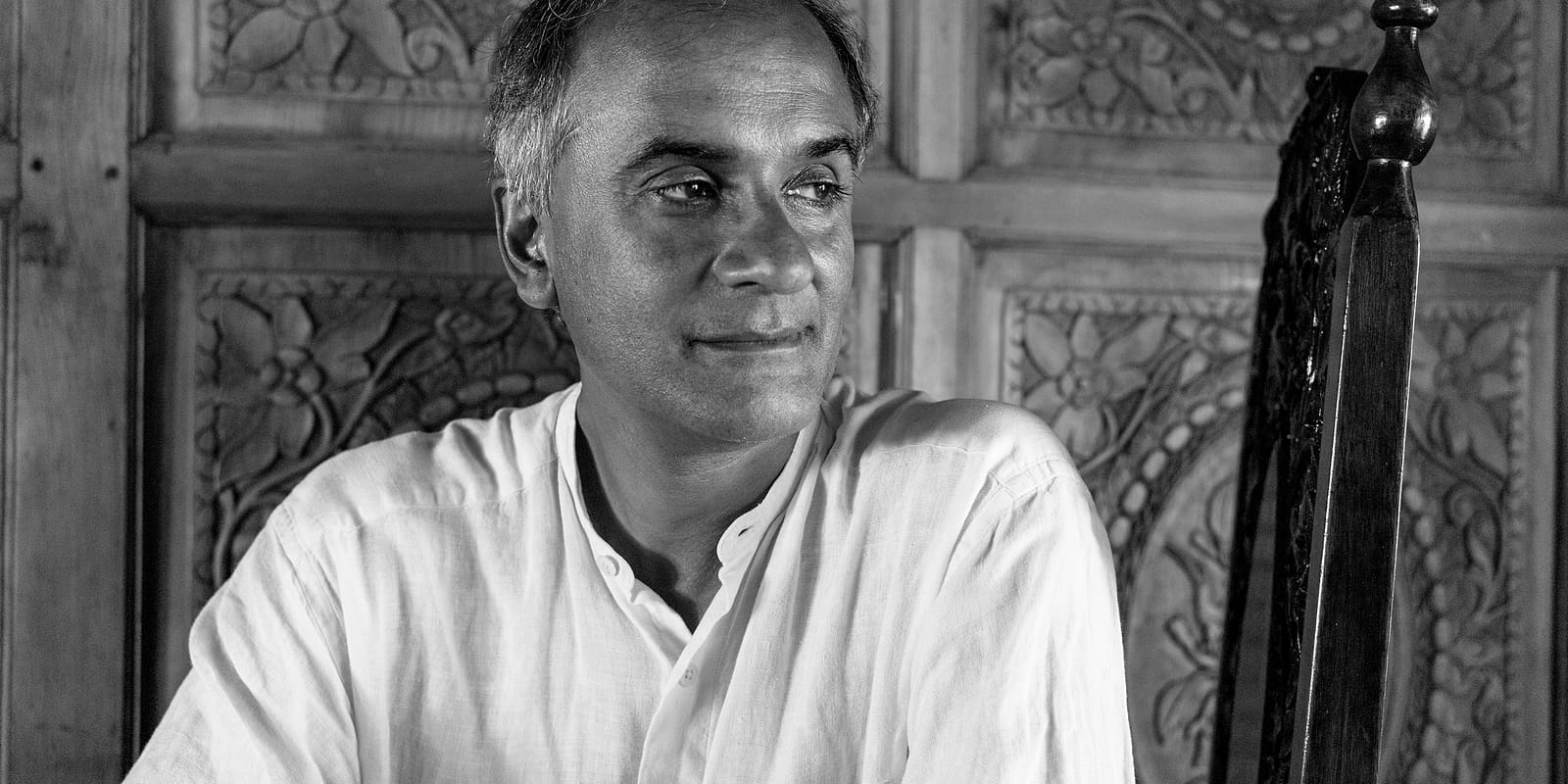

On May 23, acclaimed travel writer Pico Iyer joins Portland Japanese Garden’s Curator Emerita Diane Durston for an afternoon of conversation about seasons and the constancy of change. Japanese Garden Training Center Director Kristin Faurest, Ph.D., spoke with the author about the ideas and experiences that inform his work.

KF: Your newest book is considered a memoir, a travel book, and many other things. What were the new places that this year of family grief and loss took you to? What new side of Japan revealed itself to you during this time?

PI: Part of the beauty of Japan for me has always lain in the fact that the entire society is organized around the seasons; that cycle of changelessness and change becomes almost the frame or chapel around which everyone organizes her life. The cherry-blossoms every spring teach us how to find joy in a world of sorrows, as the Buddhists have it; the maple-leaves, in some respects, teach us how to die, but, also, how to find beauty and wonder in the fact that nothing lasts. So I’d always cherished the way that all Japan comes to resemble not a desert but a garden.

When I wrote a book about my first year there, thirty years ago, I took great pains to subtitle it, “Four Seasons in Kyoto,” and to include a fifth season, to remind the reader and myself that the seasonal cycle never concludes, and that every autumn marks the first step towards a new spring.

When my father-in-law was suddenly taken into hospital, therefore, at 91, and died three days later, I was propelled into the heart of this wisdom as it is experienced in Japan and into the rites that this old and deep society has refined over centuries to help each one of us deal with death. I was reminded how young and unanchored my home society can be by comparison; how practical and efficient the Japanese are in celebrating a life and finding an outlet for grief.

I was startled at how quickly a body is disposed of—and how in Japan a spirit is never let go of, but given fresh tea and snacks every morning long after a body is gone.

KF: Enduring a loss is something people around the world experience. What of that time felt universal and familiar, and what felt particularly and uniquely Japanese?

What was most important to me was the universal aspect. I worry that Japan, in its forms and manners, is more foreign to us than almost anywhere, and feels more like another planet than do China or South Korea or Rwanda or Brazil.

A Japanese garden has all kinds of features that couldn’t be more different from the gardens we know in France or England; it would never be mistaken for a garden in Suzhou or Seoul, either. And yet the emotions it stirs and the intuitions it awakens are, of course, ones that each of us knows quite intimately, wherever we may happen to be.

KF: You have described home as not so much a piece of soil but a piece of soul. What makes us identify a place – or places — as home? How do we find that piece of soul?

PI: Home, for me, is whatever lives inside us, whatever really sustains and grounds us. In my case that would be my mother, the wife I’ve known for 32 years, my favorite Leonard Cohen song, the copy of The Quiet American I often bundle around with me in my carry-on.

Home for me has never had so much to do with where I live as with how I live and what gives me life and purpose.

And as a typical, post-national mongrel—born and raised in England, to parents from India, and official resident since the age of seven in the U.S.—I think of home as a collage, a work-in-progress that is constantly expanding, a sentence that never ends. My deepest home lies in Japan, a place with which I have no official connection, but which makes deepest sense to me at the level of heart and soul. We all have these secret homes, and in the global age, a few of us are lucky enough to be able to root ourselves in the places that touch us most deeply.

My deepest home lies in Japan, a place with which I have no official connection, but which makes deepest sense to me at the level of heart and soul.

KF: What are the places in the world you haven’t yet explored that you’d like to? What are the favorite places you’d like to revisit to see how time and experience have changed your perception of them?

PI: There are so many places I’ve never been to, and would love to go to, and surely never will. But I’ve been lucky to see a little of the world and, as you say, I do like to revisit places in much the same way that I prefer to visit old friends now than to cast around for new ones and I love to reread books I’ve already loved more than to try to find new epiphanies.

Cuba has long been a place very close to me; I used to go to Havana every few months in the 1980s and early 1990s, and it became an essential part of my life, in part because it’s so complex and ambiguous, like a song that keeps going around in one’s head and of which one can never be free. And I have been traveling to Tibet since 1985, and talking and traveling with the Dalai Lama regularly since 1974, so following the destiny of that rare and irreplaceable culture has been essential to me.

The single most glamorous and refined place I’ve ever visited, not least in its gardens, is Iran. I once published a 370-page novel partly set there, though I’d never been!

KF: You will of course be sharing the stage here with us with Portland Japanese Garden’s Curator Emerita, Diane Durston. Could you share a bit about the context of your relationship?

For every visitor to Kyoto, there’s really only one author to read, Diane Durston. Like every wide-eyed newcomer, I picked up a copy of Diane’s book on Old Kyoto soon after I arrived, and used it as an atlas to all the ancient and sometimes imperiled traditions and backstreets of Kyoto to which Diane, with her fluent Japanese and sympathetic manner, had rich access. Later I would take all the walks around Kyoto outlined in other of her books, never guessing that one day I might meet this legendary figure, of whom I’d heard much even before I arrived in a small bare room along the eastern hills in 1987.

The one foreign writer on Japan I most cherish on every subject, Donald Richie (an American who lived there for the better part of 66 years, from 1947 till 2013) told me, the one time I met him, “If Diane doesn’t write, it’s a sin.” As a beautiful and brilliant writer himself, he knew that she was the one we all most needed to listen to.

KF: Have I left anything out?

PI: Given that the background of my coming book is grief and loss, is that its central action is more or less ping-pong and the wild games that erupt twice a week around some worn green tables as I and my even more elderly Japanese neighbors take one another on in furious games of doubles! What Japan has taught me most—and this is the subject of Autumn Light—is how to keep finding delight and even youthfulness in the midst of the ongoing cycle of the seasons and the falling away of so much of what one loves. So in this book ping-pong is the sun, the perpetual spring, to set off against the mounting autumn outside (and inside), and something that ensures that the feeling of the book is as close to Midsummer Night’s Dream as to The Winter’s Tale. And my next book on Japan will be coming at the end of the summer.

So that, too, is a reminder that nothing ever ends, really, and every enquiry just keeps unfolding, entering some new dimension or key.

Join Pico Iyer and Diane Durston at the Garden May 23 for “Autumn Light: Observing the Seasons and Changes in Japan.” The event is part of the Garden+ Lecture Series and is presented by the Japanese Garden Training Center. Tickets available at japanesegarden.org.